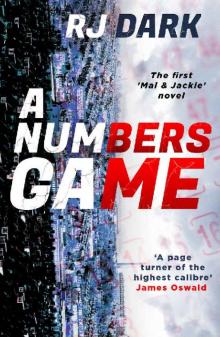

A Numbers Game (Mal & Jackie Book 1) Read online

A Numbers Game

RJ Dark

Published by Wavesback.

An imprint of Havsstad Media Ltd.

Saffron House, Knighton Road, Wembury, Plymouth, PL9 0JD, United Kingdom.

www.everybodywavesback.com

Copyright © RJ Dark 2020

RJ Dark has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers.

ISBN: 978 1 8384537 1 8

eBook ISBN: 978 1 8384537 0 1

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places and events other than those clearly in the public domain, are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

For Lindy, who makes all this possible.

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

1

MONDAY

The week started unseasonably warm for spring and with my best friend sitting on top of me, threatening violence. From there it only went downhill. But that’s what it’s like when you deal with the dead; sometimes it feels like all they want is for you to join them.

Slap.

‘Where’s my money?’

‘Jackie, I don’t—’

Slap.

‘Where. Is. My. Money?’

‘Jackie, I can’t—’

Slap.

‘Your little brown friend wants his money.’

Slap

‘Why do you even call yourself that, “little brown friend”?’

Slap

‘To annoy lefties like you, Mal. Where’s my money?’

Slap.

‘You always say you’re a lefty.’

‘Don’t change the subject. My money?’

Slap.

‘This doesn’t even hurt.’

Slap.

‘That’s ‘cos I know you get a weird kick out of taking a beating.’

Slap.

‘Jackie, will you—’

Slap.

‘My money, Malachite Jones. Now. Give it me.’

So much about this situation annoyed me.

That he called himself my ‘little brown friend’ precisely because he knew it made me uncomfortable, even though he wasn’t little, not anymore. Though he was brown, his grandparents had come from the Punjab, but the nearest Jackie had ever been to his heritage was the Jaflong Taste Indian takeaway.

That annoyed me.

The fact I had to pay him protection money, just like everyone else who ran a business in the area, even though we were supposed to be best friends because, ‘I can’t show favouritism, Mal, can I? People would think I was weak.’

That annoyed me.

Call Jackie Singh Khattar weak and you were liable to vanish from the face of the earth.

The fact he used my full name, Malachite, when he knew I hated it. Because what sort of person names their son Malachite when they are going to grow up on one of the roughest council estates in England?

That annoyed me. Anyone calling me Malachite annoyed me.

The fact I wouldn’t be able to eat if I gave Jackie the money, and he knew that and would give it right back because ‘it’s about the gesture not the cash.’ Well, that annoyed me almost beyond belief.

And the slapping, that was quite annoying as well.

That’s the thing about friends; they know how to push your buttons. That was one of the reasons I chose not to have many. Not that I was overrun with offers, but still.

Slap.

‘Alright! Fifty quid, in the top drawer.’

‘Well, get it then, Mal.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because you’re sat on me.’

He stared at me. He was a weird-looking man, Jackie. He was big now, but I always saw the ghost of the kid I’d known overlaid on the man he had become. Thin, council-house thin, never-had-enough-to-eat thin, never-had-the-right-things-to-eat thin. His cheekbones were like blades, his eyes sunken and his skin, light enough he could (and did) pretend he was just a very well-tanned white boy when he wished – as long as he kept out the sun. When you saw him up close, he had wrinkles around his eyes and mouth, like laugh lines but he never laughed much. Smiled a lot, but not a big laugher, our Jackie.

He stood, pushing long, silky black hair out of his face, his arms thick with muscle after years in the army. He was wearing Fred Perry knock-offs today, in pastels; yellow trousers and a clashing pink jumper. He wasn’t tall, standing five foot eight in his ugly expensive cheap clothes. He wore good shoes though; that was, he said, how you knew he had money. Good money wore good shoes, and when he said that I heard his mother’s voice. Not his real mother, she died when he was two. His foster mother.

We never talked about her.

Sometimes people mistook Jackie’s blasé attitude for him being a pushover. They only ever did it once though, and if they looked in his eyes first, they didn’t do it at all.

I stood, chalk to Jackie’s cheese. Where he was more muscular I was taller, which I liked, as it felt like a bit of an advantage. Same long black hair, but my colour came from a bottle not genetics, which he thought was funny. I didn’t have the ghost of a hungry kid haunting my psyche either; I’d never wanted for anything material when I grew up. I wore black, it was an easy colour to wear and it suited my calling: vicars wore black, undertakers wore black, I wore black.

The desk in my office, the one that had Jackie’s money in it, was made in 1832, the same year the second cholera epidemic struck London, and constructed from oak ship timbers, though I’d never been able to pinpoint which ship. It was heavy, dark, imposing-looking. I like old things, though I’m rarely around them. Unless you count pensioners, who are most of my clientele. I had Jackie’s money in the hidden compartment in the back of the top-right drawer, always did. Sometimes I just liked to make him work for it. Payment was a foregone conclusion.

‘Here.’

He took it, counted it.

‘I can’t believe you still count it, we’ve been doing this for years.’

‘You’re a crook, Mal. Of course I count it.’

‘I am not a crook. I provide bereavement counselling.’

‘Fucking crook,’ he said. ‘Takes one to know one. Anyway, if I take this, right’ – he thumbed through the notes – old tenners, though I knew he liked twenties, or even better a fifty that he could flash about – ‘can you still pay your bills?’

‘Yes. I can meet my responsibilities. I just won’t be able to eat.’

He slipped the money into his pocket. Smiled at me.

‘You did hear me say I wouldn’t be able to eat.’

He nodded.

&nb

sp; ‘Well?’ I held my hand out.

‘You want me to give you some skin, brother?’ He dropped into a cod Jamaican accent. Jackie had a remarkable talent for mimicry.

‘I want to eat.’

‘You can. Girl called Janine Killingham – she’ll drop by later for you to con.’

‘It’s called a consult.’ I slipped the words out between gritted teeth. Half the skill in dealing with Jackie was in not rising to the bait. ‘That name sounds familiar.’

Which should have been a warning.

‘Her big sister, Helen, was a model. Bit of a looker, nice tits. I ‘ad her you know – or she had me, I was never sure. Night before her wedding.’

‘Classy.’

‘You know me, any hole in a port, innit.’ Big grin, such perfect white teeth. ‘Anyway, she needs help. You talk to her, help her out, and we might do alright out of it. Mates’ rates too – she’s from the Edge.’

‘I’m trying to avoid clients from Blades Edge.’

‘If you want to eat, then you’ll see Janine. She’ll pay you cash up front. Don’t worry, you won’t get stiffed.’

‘I don’t want to deal with the Edge.’

He stared at me. Blades Edge was the biggest council estate in the North. It sat in the shadow of a hill, half of it had been carved away in the 1960s to build the estate, creating a huge chalk cliff that loomed over the houses. That was where it got its name, from the hill, The Blade. I’d grown up on that estate, been bullied mercilessly on it, spent every day walking the sparsely grassed fields mined with dogshit or over pavements of cheap concrete that crumbled underfoot. Spent the first thirteen years of my life absolutely terrified every time I left the house.

Mostly terrified of Jackie back then. But things change; everything changes. Except Blades Edge. Or rather it does change, just not for the better.

A good half of it was derelict now. The whole place was marked for renewal by the council but that had got bogged down in legal problems with the people who had bought their houses, and there was a travellers’ site that the council couldn’t move. So, as ever, plans that were meant to make the place better only ended up running it further into the ground. Empty houses stood out on the streets like bad teeth in among, well, teeth that weren’t too good to start off with.

A new client from Blades Edge. Should have been a warning.

I should have said no.

‘Okay, I’ll see her.’

‘Good lad,’ said Jackie, and he left, letting the door close slowly behind him. I saw a flash of red from the Ferrari he was driving this week. A second later Beryl came out of the back office. My secretary, or I called her that. She was a big woman in every way: loud, liked her food, unafraid to speak her mind.

‘He took the last of your money,’ she said.

‘Yep.’

‘And you let him?’

‘Yep.’

‘Ponce.’

‘You mean me or him?’

‘The both of you. And you better not have given him my wages.’

‘I didn’t.’

‘Good.’

‘What do you know about Janine Killingham, Beryl?’

‘That model’s little sister?’

‘Yes.’

‘That Helen Killingham has an open marriage, you know. I read it in the paper. What a slut.’

‘People should do what makes them happy, Beryl.’

‘You like drugs.’

‘I did.’

‘Try ‘em again and I’ll kick fuck out of you. I’m not soft-hearted like yer mate.’

‘I know that, Beryl.’

‘Just make sure you do bloody know.’

‘I do. Now, Janine Killingham?’

‘Bit of a cow, or she was.’ Beryl took a cigarette from a packet in her pocket but didn’t light up inside, not anymore. ‘She took up with one of the Stanbecks, married him.’

‘So she’s not actually called Janine Killingham anymore?’

‘No, Janine Stanbeck.’

I sighed. The Stanbecks ran all the crime on Blades Edge, and a lot of the surrounding areas. I decided I would kill Jackie next time I saw him.

‘Married Larry Stanbeck, Mick’s son,’ Beryl said.

Mick Stanbeck, or Trolley Mick as most knew him, ran the Stanbecks. I decided I would kill Jackie twice when I saw him.

‘He probably liked to knock her about, but that’s the Stanbecks for you. Bunch of wankers think women are punch bags. Fucking Irish though, what can you expect.’

‘You say the same about Muslims.’

‘Aye. Arseholes.’

‘Any feelings on Mormons?’

‘Are they men?’

‘Some of them are.

‘Well, there’s your problem, only reason I’m queer is men are such shits.’

‘Thank you.’

She paused then. I’d like to say it was because she was aware she’d overstepped some mark with her casual racism but Beryl didn’t have boundaries the way other people did. She opened her mouth and said whatever was in her mind. It made her useful to me and an absolute nightmare for anyone else.

‘Why are you thanking me?’ she said, ‘I just called you a shit.’

‘Never mind, Beryl. Janine,’ I took a deep breath, ‘Stanbeck?’

‘I’m not sure you count as a man though,’ she said to the air. I stared at her, trying to see if she was joking or not, but she was unreadable. Not a woman to play poker with.

‘You were talking to me about Janine Stanbeck.’

‘She one of them morons now?’

‘Forget the Mormons, Beryl. Janine Stanbeck. She’s coming to see me. So, who died, her mum, dad? They must be getting on now.’

‘Oh no. It was her fella what died. Larry. Came off his motorbike. Died instantly, which is shit – bastard should have at least suffered a bit. Bloody Stanbecks.’

I nodded. This was exactly the reason I’d given up seeing people from the Edge. How many times can you see someone who you remember from your youth, face punched black and blue, and tell them that the man who used to beat them is on the other side; he’s happy, he loves them, he always loved them and he’s sorry for the things he did. Then take their money for straight-up lies without starting to feel like a fraud.

‘Word on the Edge is someone ran him off the road.’

If ever there was going to be a warning, that really should have been it.

For a psychic medium, I have always been very bad at seeing the future.

Jackie would say it was because I am a fraud.

And, of course, Jackie would be right.

My office is in a row of six lonely shops built in the 1930s on a busy main road. Half a mile one way and you’re on Blades Edge, half a mile the other and you hit Crais Curve, famous accident blackspot and the last thing about fifty per cent of the Edge’s joyriders see before the inside of an ambulance – or a hearse. We have a little lay-by that cars can park in just in front and all around us are woods. The strip of trees behind the shops is about five hundred metres deep, though it runs for miles in both directions. Behind that is a road, then a high wall and the grounds of an old country house that’s now a hotel and aggressively prosecutes trespassers. Next to my shop on the left is Mr Patel and his wife Nasreen who run an off-licence and newsagent’s. On the right is Oriental Promise, a Chinese takeaway run by Mr Wan, who speaks no English at all – unless he knows you and then he becomes fluent. After that is a big-name booky that is sucking cash out of people who can’t afford it at a rate I can only dream of.

At least I provide a service for your money.

The end shop of the row is a kebab and curry house called Spice ‘N’ Saucy that sells excellent kebabs and very bad curries and is manned by a constantly changing crew of polite and well-groomed young Asian men. They appear, work a few months, and then disappear, never to be seen again. It’s also a front for a lot of class B drug dealing – ‘Extra herbs on the pizza, please’ – but no one seems to care.

&n

bsp; Mr Patel used to run a shop on the Edge; it looked more like a fortress than a newsagent’s but that didn’t stop him getting robbed regularly. He was going to pack the business in until the offer of his premises here came up. Similar story for Mr Wan. They serve a lot of the same clientele but no one robs them because Jackie owns most of the block, bookies aside; we all pay rent and protection to him. Mine, Mr Patel’s and Mr Wan’s rents are far below the going rate, even if you take the protection into account. I have no idea what Spice ‘N’ Saucy pay but I suspect that if you dug hard enough, you’d find Jackie owns it. But I wouldn’t suggest digging that hard because he would find out and then he would find you and you would have a short but unpleasant conversation about why digging into his affairs is a bad idea.

My shop is nondescript from the outside; the window is entirely closed off from the street by long red velvet curtains. Inside, it’s mostly dark colours, dark-red carpet, dark desk, dark-green walls in a reproduction Victorian wallpaper that glitters in the right light, though I deliberately keep the lighting low – through faux candelabras in sconces and plenty of candles, for the mood. I did have a big chandelier, but I kept banging my head on it as the ceiling is far too low for that sort of thing.

‘She’ll be here soon,’ said Beryl. She was standing between me and the desk, a wall of badly dressed flesh with dead eyes.

‘I know.’

‘Teabags.’

‘What?’

‘We’ve no teabags.’

‘Go get some then?’ Keeping the office stocked was meant to be Beryl’s job.

‘Got work to do.’

‘Well, go later on then.’

‘Can’t work with no teabags.’

‘But you just said …’

‘Need some teabags.’

There wasn’t really any arguing with Beryl; she was like Jackie in that way, and I wondered what god I had angered to be surrounded by such strong personalities.

‘Fine, I’ll go get the tea.’

‘Good.’ I grabbed what remained of the petty cash after paying Jackie – three pounds and fifty-eight pence – and opened the door. ‘Oy.’ I turned.

‘What?’

‘Second of June 1974,’ said Beryl, as if that would mean something to me.

‘Again, Beryl, what? You’re going to have to give me some context’

A Numbers Game (Mal & Jackie Book 1)

A Numbers Game (Mal & Jackie Book 1)